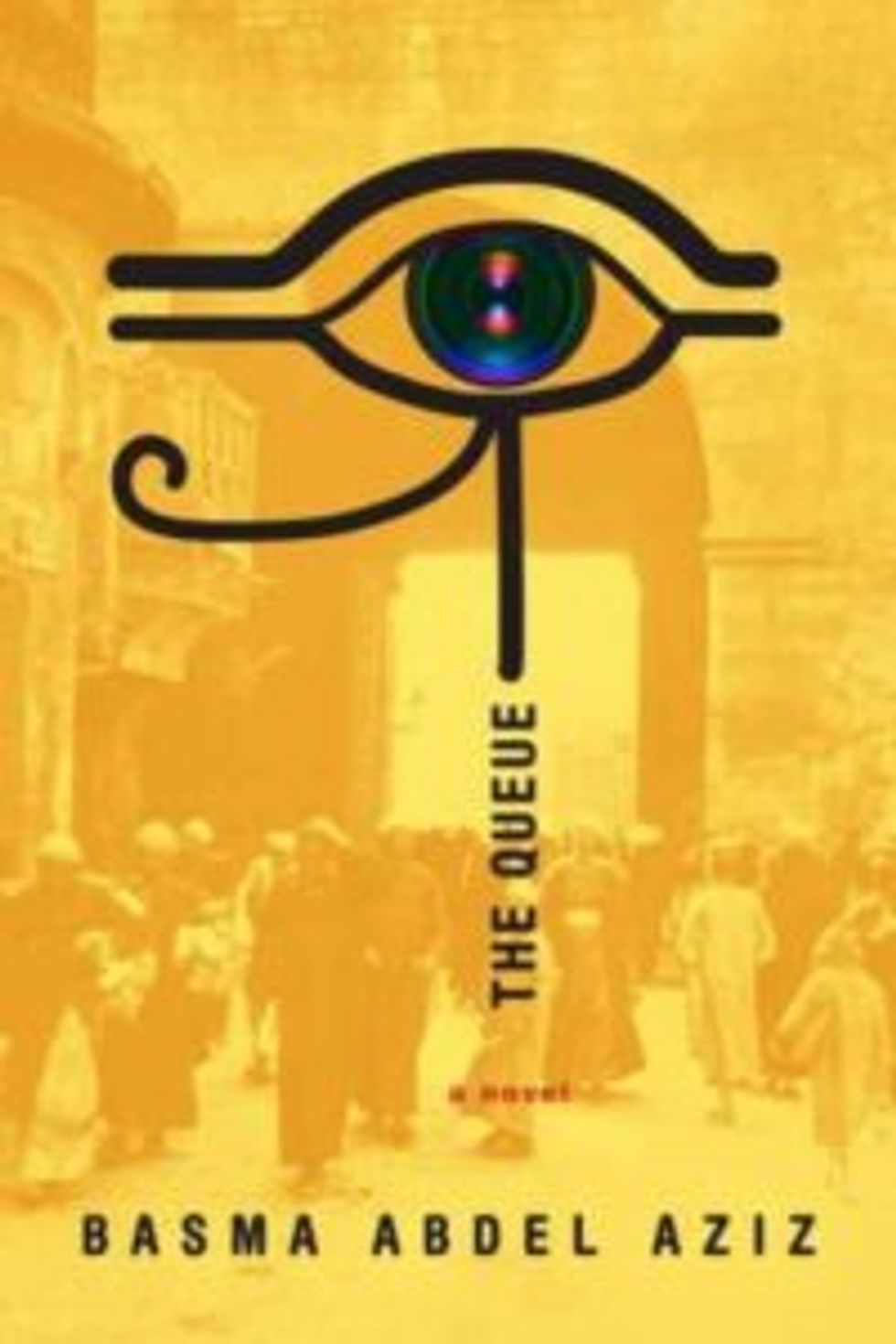

"The Queue" is a Dystopian Novel About Egypt After the Revolution

While Basma Abdel Aziz's new work starts with a bullet to the gut it is also relevant to those of us stuck on hold with an insurance agent.

When describing Basma Abdel Aziz’s novel, The Queue (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette), it’s easy to compare her to George Orwell and Franz Kafka or to use terms like “satire” and “dystopia.” And certainly, these shoes fit. But these kinds of descriptions are also a kind of trap: we know these words too well, and putting a familiar label on this novel makes it seem too familiar, giving readers permission to know what they’ll find before they start writing.

But the last thing we want is to make this novel familiar or easy, or to confine it to the realm of fiction. The Queue is the world we live in without letting ourselves to know it: to call it “satire” or “dystopia” would be to miss how real (and banal) it has already become.

We also don’t want to place this novel “out there.” Certainly, The Queue is a very Egyptian novel—unmistakably a response to the revolution that toppled Mubarak and the succession of regimes that have followed, and drenched with local references. But it’s also a novel exploring the organized passivity of a beaten-down citizenry, a people’s willingness to line up and live in optimism that the state will meet their needs, against all odds and past precedent.

In this way, while it’s certainly a novel inspired by the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution, it may also feel uncomfortably familiar the next time you find yourself on hold with a medical insurance agent, or in any way interacting with the criminal justice system. If it’s a dystopia, it’s not as far off as we might sometimes like to think, and certainly not confined to Egypt (where it’s anything but a pure satire).

As Aziz has described, she began writing the novel when she saw a long line of people waiting at the door of a closed government building:

“One sunny day, I went to Downtown Cairo, where numerous battles between revolutionaries and security forces had taken place since the revolution began in January 2011. While walking down a main street, I came across a long queue of people waiting in front of a closed governmental building. The gate to the building would certainly open shortly, I thought to myself; after all, it was nearly midday. Two hours later I walked back the way I came, only to find the same people standing exactly where they had been. They hadn’t moved.“The people seemed bound there – to that patch of ground, and to the gate which was still closed – by the hope of having their needs met…Some seemed financially comfortable, while others looked poor, there were women and men, elderly and young people, and even children playing nearby. I wondered why they stood there so long in vain. Why didn’t any of them speak up in protest or frustration about the delay; why didn’t anyone suggest they all leave?”

The question is why they keep waiting. The Queue is the answer.

Before she wrote this novel, Basma Abdel Aziz was a doctor—a psychiatrist who worked with torture victims—and as a journalist and polemicist, her subject has been the authoritarian repression of the Egyptian people. And despite a certain cautious hedging about names and dates, the alienating force of this novel—the insanity buried in a realist core—is a very specific satire of this instantly recognizable setting: The Queue is Egypt, when nothing is left of the nation-state but the military, where the only part of the government that really works is the police.

For the moment—for the permanent moment of emergency—everything else has been put on hold. If you would like to be repressed by the security forces, that can quickly be arranged; for anything else, you’ll have to wait, patiently. And so, after the revolution has been crushed, this is where the people are now united: waiting.

In terms of plot, the novel begins with a bullet in the belly of its protagonist, a man named Yehya who was shot by security forces during an unsuccessful uprising that everyone has agreed to call “the Disgraceful Events.” He finds himself in a queue, at The Gate, waiting to petition for permission to have the bullet removed.

At the time, a doctor temporarily patched him up, but the bullet itself was left inside him, and now, thanks to a new governmental edict—issued by the new ruling authority, called “The Gate”—surgeons are not allowed to remove bullets from their patient’s bodies without explicit written permission. So Yehya queues up, fighting the pain and hoping the wound doesn’t suddenly worsen: having been shot by the state, he now finds himself in line to ask the state to permit him to be treated.

The Gate does not open.

As the people wait, a host of new requirements and regulations are issued, day by day, week by week, new forms of paperwork and official certificates required for everything from the most mundane daily services to vital needs. All the paperwork must be acquired at the Gate: To change jobs, to get a death certificate, to receive a pension, to be declared a “True Citizen,” or to be officially recognized in a variety of small and large ways, all must line up at the Gate and wait for it to open.

The Gate does not open.

The Queue grows longer. The people have nowhere else to go, so they stay, day-in and day-out. The people find ways to make an impossible situation livable, by taking shifts, holding places, and eventually forming ad-hoc associations to keep the Queue in order. The Queue becomes the new status quo, as time passes and the gate stays closed; what began as a trickle of hopeful petitioners grows to a river, and then a hopeless multitude, waiting with a cruel kind of optimism that the Gate will open.

And the Gate does not open.

As time passes, and as the endless status quo stretches on, impossibly, people settle into new routines and an entire society springs up in Queue, which begins to resemble a city in its own right: some people start mini-business ventures, selling tea or phone time; for others, new social organizations help fill the time, religious, educational, political. As days become weeks and become months—and the Gate stays closed—the queue becomes a self-contained community with its own landmarks and organization, a city within the city.

But the Gate does not open.

The Queue is not an irresistible force, and the Gate is an immovable object. The fact that everyone agrees to call the uprising “the Disgraceful Events,” for example, tells us that it failed, that we are in a decidedly post-revolutionary moment of reactionary backlash. But beyond that, little is clear, neither how nor why Yehya was shot, nor what the status of the uprising is. In part, this is because no one really wants to talk about. The people are beaten down and afraid, so desperate for life to return to normalcy that they will pretend things are normal, even when they are not.

The one thing that is clear is that the revolution is over. And so, Yehya and everyone else find themselves returning to the very spaces where before there had been revolutionary assemblies, returning in the masses that had once demanded change and an end to the previous regime, only now they are returning as self-organizing assemblies of patient petitioners, presenting themselves in an endless queue, waiting for the Gate to open and hear them.

But still, the Gate does not open.

If the line of hapless petitioners reminds you of Kafka’s “Before the Law”—and if the subsequent revelation that The Gate is monitoring and spying on the people in line (and even torturing and brainwashing those whose inquiries go too far) recalls Orwell’s 1984, the most chilling aspect of this novel is how normal it all feels, and how quickly the new regime becomes frighteningly normal. And here is where the novel feels least dystopic, and most banal: anyone who has watched time disappear into the endless absurdity of an un-hurried medical bureaucracy will know that one needn’t be shot by security forces in a dystopian to be killed by the state. Closed offices, long lines, and opaque and nonsensical regulations, can all kill, too, and in the most boring and banal ways. For all the spectacular violence of the security forces, perhaps the most murderous thing the Gate can do is: nothing at all.

Yet, still, the Gate does not open.

For Yehya, the bullet lodged in his abdomen is a reality principle in the midst of a reality being scrubbed into orthodoxy. At first, anyone who was shot must have deserved it, for rioting against security and order; then, suddenly, no one was ever shot at all, as the doctors he needs to remove the bullet assure him (“No one was injured by any bullet that day or the day after or any other day, do you understand?”). And so, as the officially nonexistent bullet cuts into his intestinal lining, and his condition worsens, day by day, Yehya’s struggle to get medical care is met not with open repression but with a deadly and maddening non-responsiveness. A bullet could be incriminating if the government denies anyone was shot, but since officially there were no bullets, it is only natural for the state to prohibit surgeries to remove bullets from people’s bodies. In this way, reality is no problem at all: it will solve itself, simply, when Yehya dies.

And so, the Gate cannot open.

And yet… how long can this continue? The novel drags on, as it must, because so does life: the queue continues to grow, and so does The Queue, and we, the reader, wait for some kind of resolution, some kind of ending. Will The Gate open? Will there be another uprising? Neither seems likely: Basma Abdel Aziz’s novel shows us the society of the impossible normal, as the Gate does not open, and as the people unite in its shadow.

And as we watch bodies and minds meet their limit, we watch some of them break, but we note that some do not: some bodies grow, from solitary individuals to cooperative pairs and then small groups and then larger groups. A nation reduced to the subjects of a security state begins, little by little, to crawl towards a knowledge of itself, and of a new sense of what that self it.

The Gate does not Open. But The Queue begins to move.

And so, at the heart of The Queue is a reality born of despair: there a limit to how much insanity the mind can take, a limit to how long the people will wait. There is a breaking point. And while the ending of the novel only suggests—only hints—that something has begun to change, this novel about normal people is far less about the banality of authoritarian evil than about the mundanity of resistance. Like a bullet in the belly, the Queue will move; the people will begin to push. Some may die, even many. But the people begin to move.

The Gate cannot open. It will open.