Liberian MC & Producer Shadow On Making Music After The Ebola Outbreak

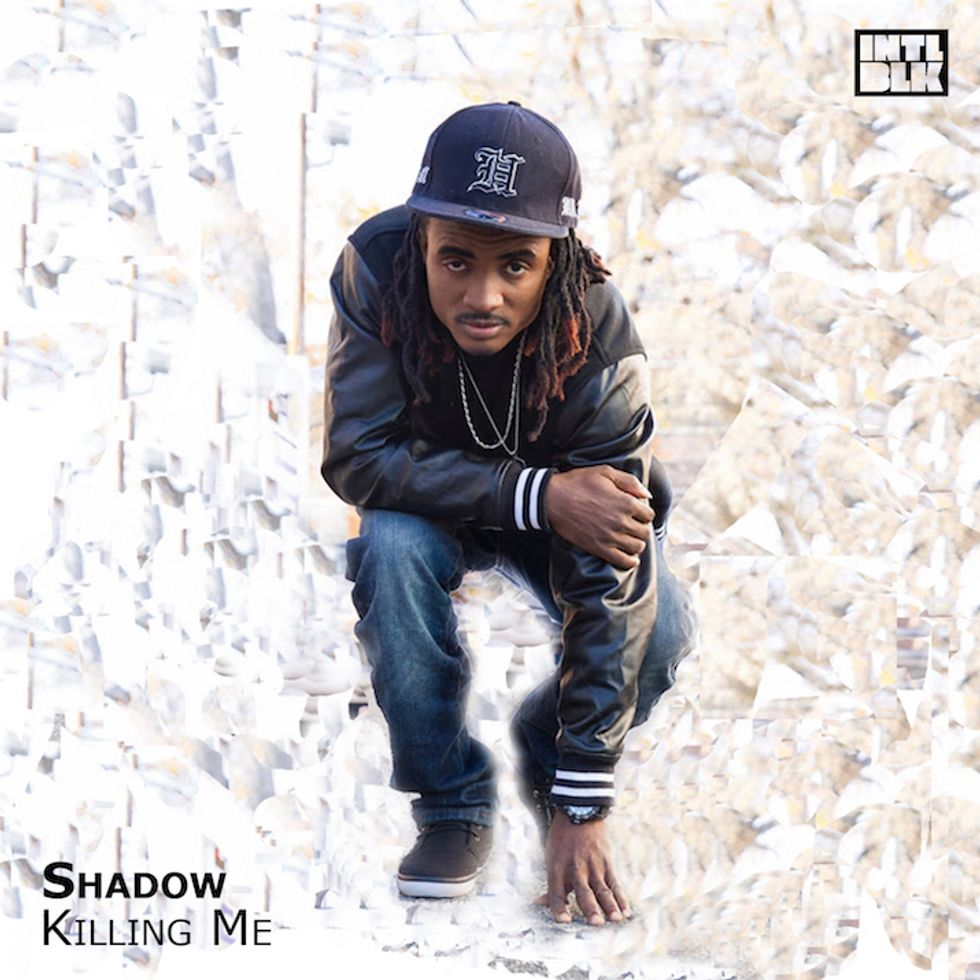

We speak with Shadow about making music in a refugee camp, the state of Liberian music and his new single "Killing Me."

Back in 2014, Liberian rapper and producer Shadow was on countless major publications for his awareness track "Ebola In Town," a song that became a hit and served to warn the country against the looming virus. He's now returning with "Killing Me," a shuffling new track about the beauty of African women that juggles influences from hipco, Liberia's take on hip-hop, and the high-energy dance music of gbema.

Born and raised in Monrovia, Shadow was forced to flee Liberia after the outbreak of the Second Liberian Civil War and ended up in Buduburam, a refugee camp outside of Accra. It was there that he set up a studio and started making music with other refugees. The MC returned to Liberia in 2012 with the aim to tap into Monrovia's growing music scene, but was forced to leave again in 2014 after the ebola epidemic caused a ban on public gatherings and, with that, all concerts, making it impossible for musicians to perform and make money.

We spoke with Shadow below about the state of music in Liberia and his new single "Killing Me," which is being released alongside remixes from Chief Boima and Subculture Sounds on "pan-Afro anarchist pop" label INTL BLK records.

You fled Liberia after the break out of the second civil war and were living in the Buduburam refugee camp, where you also set up a recording studio. Can you tell us a little bit about the experience of living and making music in Buduburam?

Running for your life is one thing, but living as a refugee is a really sad condition. Living in the Buduburam camp as a teenager without parents or relatives—only other people and kids like myself with different stories about their lives—wasn't easy.

Finding food and a place to lay our heads was a mystery, but with the grace of God I made it out of there alive, learned and impacted the lives of others. Though it wasn't easy, I was able to establish a group called Shadow's Entertainment and a recording studio with over 50 members comprised of young and talented refugee kids, some of which have grown to be Liberian superstars.

The studio’s first international project was done in collaboration with the University of Alberta, Canada headed by Professor Michael Frishkopf.

"Ebola In Town" got a lot of international media attention in 2014. What are your thoughts on the song and its reception now?

I think the song drove a lot of people toward Liberian music. It's the first piece of Liberian music that has ever gotten this much attention from news networks, social media and individuals around the world. Everyone that listened or read about the song had their own views, but the song served as a gateway to Liberian music.

How did you first get into music growing up as a kid in Monrovia?

My love for music and the whole entertainment thing started from dancing at the age of 7. From there, I started learning other people’s songs by rapping and singing over them like they were my own. I’d perform them at community talent shows and local schools' rap and dance competitions.

I loved hip-hop and R&B—my favorite artists at the time were Tupac Shakur, DMX, LL Cool J, Joe Thomas and Michael Bolton. I started writing, recording and performing my own demo songs on hip-hop instrumentals and moved to Ghana in March of 2002, to kick start music as a full-time career.

How would you describe the sound of hipco and gbema to someone that hasn't heard it?

Hipco music originated from hip-hop. The hipco beats sound more like hip-hop beats, but they’re a little different because of the addition of a few local instruments to the production to give it that afro feel. The style of rapping in hipco is the same as hip-hop rap, but the words used in the rap are in Liberian English, called colloqua, and our local dialects. So, hipco is the mixture of the local Liberian rap on a hip-hop beat mixed with few extra instruments.

Gbema is little more different from normal African traditional music because it's very fast tempoed music with lots of congos, bongos, kick drums, rhythm guitars and bass. Gbema beats are fast but the singers sing slow to relax the song. Gbema is sung in both colloqua or dialect, and the dance is either fast or slow depending on the mood.

What would you say the current state of Liberian music is?

I can say Liberian music is doing really well when compareed to few years back, the music is gaining its attention. It’s getting to the point that the world can't ignore it. It's now crossed borders, not only for Liberians listeners but for all music lovers.

Tell us about "Killing Me." How did the track come about?

The song “Killing Me” came about at the time we Liberian musicians both home and away were all looking for our true identity in music—something that we could use and call our own style of music. Though the Gbema style of music was around, we as young up-and-coming musicians at the time were also very influenced by music from other countries across Africa and America.

So one day I was alone in my studio in the refugee camp and this idea came to me about making a beat that would sound different from what I've been making. Something that would stand out and make an impact. The song is about the beauty of African women. The way which they take care of men, how crazy guys can go from looking at them, in general, the song is about appreciating our women.

You're now Philadelphia-based, how has the reception to hipco music been in the US?

When I got to the USA late may 2014, there was not lots of Liberian music been played, but with the effort of everyone who believes in what we do, hipco, gbema and every other Liberia music is now been played at almost every African party. From my point of view the music is doing extremely well.