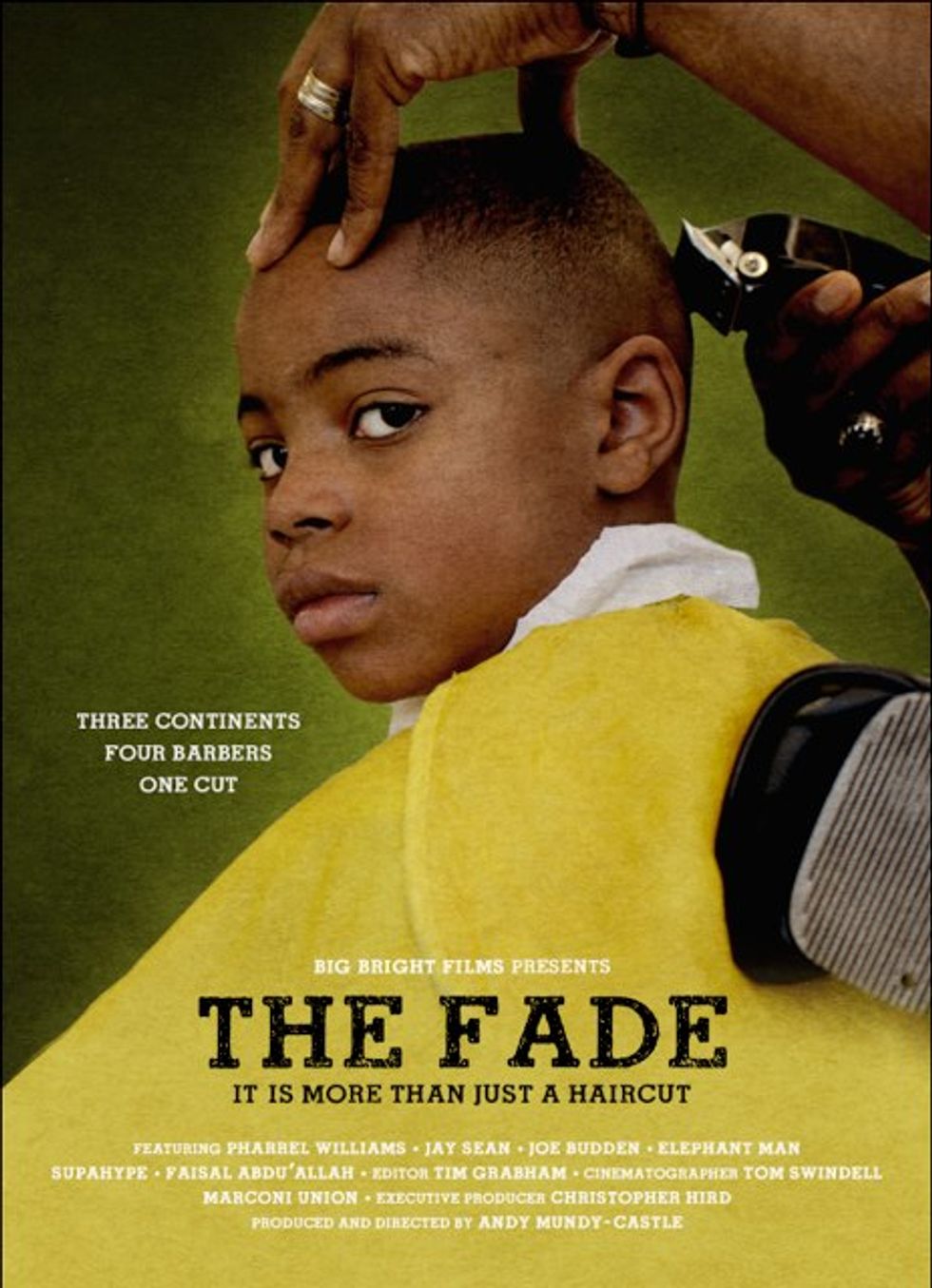

Film: 'The Fade - Its More than Just A Haircut'

Review of black film 'The Fade' by Andy Mundy Castle. Explores the artistry of barbering across the African diaspora, because It's more than just a haircut.

Offori Upac’ Mensah owns a small barbershop in Accra which allows him to have a decent life and save for his daughter’s education while he teaches boxing classes in his spare time and dreams of becoming a singer. Johnny ‘Cakes’ Castellanos, who everybody calls “Hollywood”, is a workaholic, taking helicopters and private jets around the US to meet the needs of his VIPs while keeping his fashion boutique in New Jersey rolling with an ambitious staff. Shawn Powis is a different kind of itinerant barber, forced by the chaotic but insouciant pace of Jamaica to have his bag of tools ever ready to rush off to cut and shave his customers, many of whom belong to the music community. Faisal Abdu’Allah, a recognized artist from London’s African Diaspora scene, opened his own shop after finishing art school as a space “where anything can happen,” and it has become the inspiration and monetary base for his creative work.

[embed width="620"][/embed]

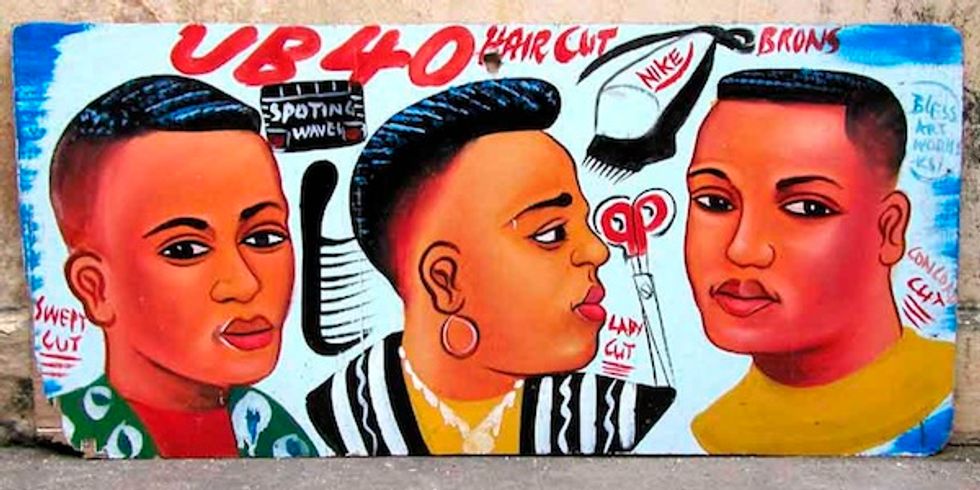

A Brit of African descent, Andy Mundy-Castle is the director of The Fade, a documentary that follows the lives of these four barbers around the world over the course of seven days. The independent film and television producer, who holds a Masters in Documentary from the Goldsmith College of the University of London, is presenting this brand new documentary, his first for the big screen, in NYC this February. His previous experience in animation can be seen in the opening images: a razor slicing the distances separating Accra & Kingston and Englewood & London, the sites where the four protagonists ply their trade, which marks the commonalities in their cultural heritage as the credits appear superimposed over afro picks, combs and scissors.

The audience follows the lives of these young men, rendered in a vibrant, quick-cut editing style, discovering numerous similarities in their work, particularly in the intimacy established between barber and client, as well as broad disparities in their backgrounds and individual aspirations. The film is structured around six chapters, each composed of four vignettes starting in Ghana, moving to New Jersey and Jamaica, and finishing in England. These chapters could have been named as follows: presentation, philosophy of life, passions and dreams, outside the shop, important clients, and miscellanea. They are followed by a short epilogue featuring the four men staring into the waters of the Atlantic, rich with memories of hope and despair that bring together all people of African roots, each from his respective shore.

Throughout the film, the viewer is party to countless clever asides from clients, coworkers, and the barbers themselves, in a confidential space from which family and friends are excluded. The ability to listen and share, supported by great manual and creative skills, have made the best barber shops a kind of sacred space for ages, where the customer may express himself freely and enjoy the sympathetic responses of a chorus of listeners and of the barber himself in his role as confidante and counselor; this is an aspect of the profession that cannot be altered by new technologies or trendy products.

Barbershops have also long served as a focal point for the transmission of stories and news. In the words of noted rapper and producer Pharrell Williams, the barbershop is the “hood Twitter.” It is not idle talk when Faisal Abdu’Allah affirms, on being invited to the CAAM gallery in the Canary Islands to present his own retrospective: “my shop is a living museum. There is the place where I find my stories both as an artist and a barber.” The barbershop is also important as a democratic space where even the rich and famous are brought down to the level of the common man. As an African proverb states: “Even the high and noble bow before the barber”.

Patronizing preconceptions may still relegate such realms as fashion design and hair styling to a second tier of artistic activity — thankfully, though, this has begun to change — but the processes of making an art object and of giving a perfect haircut share a great deal in common, and it's clear that for the protagonists of the film, their profession has a much deeper meaning than a mere job. Offori Upac’ Mensah, thinking from Ghana about his compatriots, says: “if I would meet other barbers around the world, I would tell them to keep the spirit of barbering alive.” In the coda to the movie’s final scene, a New Jersey customer looks directly into the camera and offers the following closing words: “If you have an ability, use it to the fullest, and keep going.” There is no other secret to mastery, and very few professions in which human beings commit greater trust. Who else would you let lay a razor against your neck?

Follow the film's progress on Facebook and @thefadefilm and catch it when you can.